Reaching Nova Scotia’s 53% emissions reduction target by 2030

Larry Hughes

AllNovaScotia.com

10 April 2022

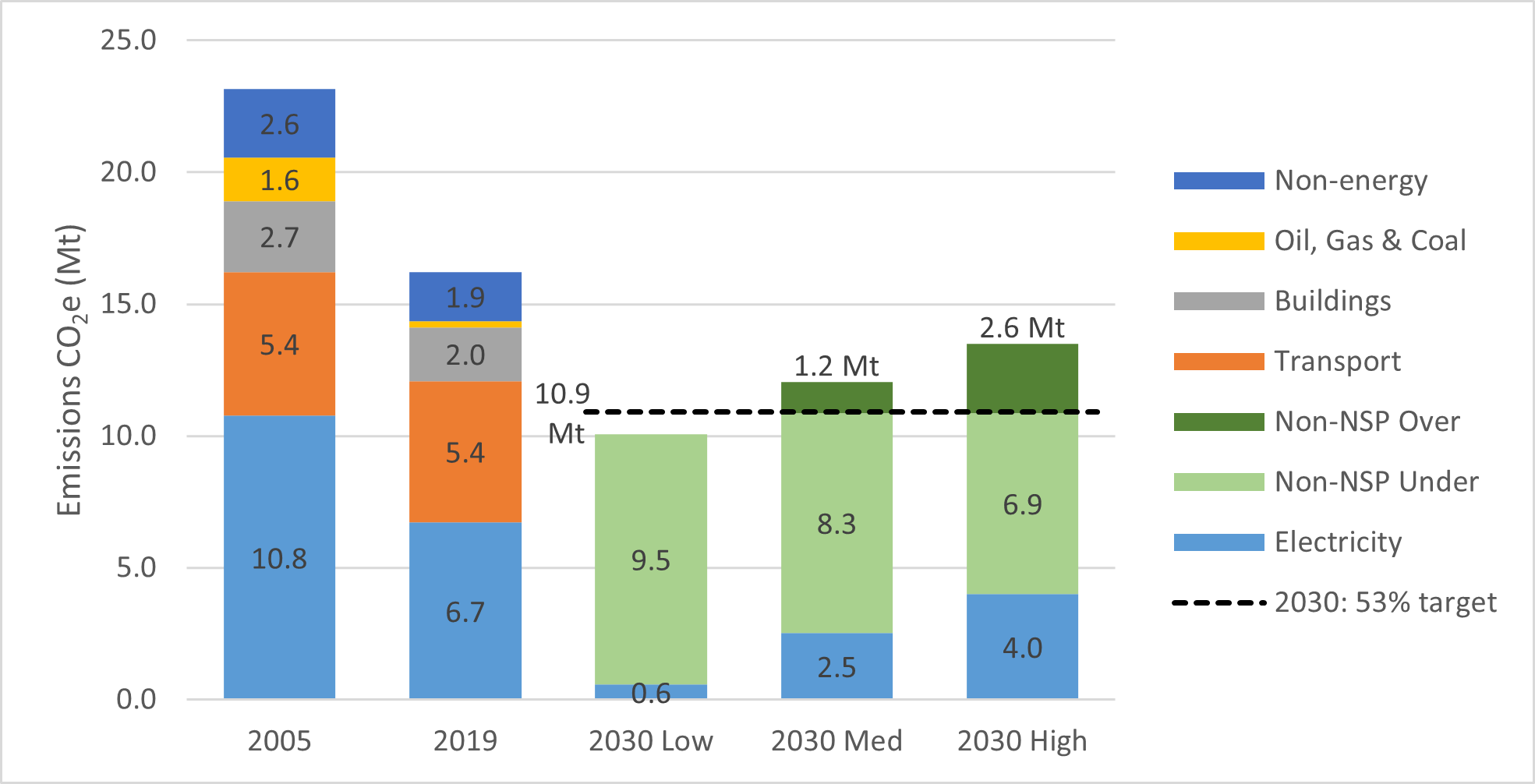

Both the previous Nova Scotia Liberal and the current Progressive Conservative governments have passed legislation committing the province to achieving a 53% reduction in emissions by 2030 from its 2005 levels.

In 2019, almost 90% of Nova Scotia’s greenhouse gas emissions came from energy production and use in three sectors: electricity production (6.7 megatonnes), transportation (5.4 megatonnes), and buildings (2 megatonnes).

Although there are numerous ways of reaching the 53% target, the one being pursued by the provincial government is the Atlantic Loop.

When completed, the Atlantic Loop is to bring hydroelectricity from Hydro Québec to Nova Scotia.

In Nova Scotia Power’s Integrated Resource Plan, the best-case scenario shows its 2030 emissions to be about half-a-megatonne, the result of eliminating the use of coal and increasing renewable electricity from local wind and imported hydroelectricity.

In doing so, Nova Scotia will have surpassed its 53% reduction target, regardless of any emission decreases in any other sectors of the provincial economy.

However, as I wrote in a submission to last summer’s public consultations held by the Nova Scotia Department of Climate Change and Environment, “It is absurd that the province’s goal of a 53% reduction in emissions in less than 10 years is based on a policy of hope that the Atlantic Loop will come to fruition”.

Recent events have confirmed my concerns.

In response to requests from New Brunswick Premier Blaine Higgs and Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston this past January, Dominic LeBlanc, federal Intergovernmental Affairs minister, indicated that the federal government would not cover the costs of the $5 billion Atlantic Loop without further technical information.

At the Council of Atlantic Premiers’ meeting in mid-March, Premier Higgs observed it would take seven or eight years, or even longer before the Atlantic Loop would be functional.

Higgs also pushed for regional solutions, presumably in reference to New Brunswick’s bet on small modular reactors.

The federal government’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan, released a week after the Premiers’ meeting raised further doubts that the Atlantic Loop will be completed by 2030. For example, the federal Plan intends to continue funding studies on projects such as the Atlantic Loop until 2025.

Moreover, it is unlikely the federal government would spend $5 billion on the Atlantic Loop when its Canada-wide 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan is budgeted at $9.1 billion.

When questioned about alternatives to the Atlantic Loop, Premier Houston noted that when power from Muskrat Falls begins to flow without interruption, 60% of Nova Scotia Power’s electricity will come from renewables. When the next tranche of wind comes on-line in 2025, renewable electricity will increase to 70%.

The question not asked was, what will this mean for Nova Scotia’s emissions?

In Nova Scotia Power’s best-case scenario for 2029 (the year before the Atlantic Loop should be completed), its emissions will have declined to about 1.9 megatonnes.

This would reduce the province’s emissions to about 50% below 2005 levels, just shy of the 53% target.

To reach the target, the province’s other emitting sources would need to reduce their current emissions by about half-a-megatonne by 2030.

This could be done by, for example, a combination of shuttering offshore energy exploration and production, and increasing Demand-Side Management programs to restructure residential heating from oil heat to electric heat pumps.

Consequently, about 10% of the province’s electricity would still come from coal. By contrast, wind would meet almost 36% of the demand.

There would undoubtedly be objections to Nova Scotia Power’s continued use of coal. But since the source of a carbon dioxide molecule does not determine its heat trapping potential, how the 53% target is met should not matter.

But even if the Atlantic Loop is completed by 2030, there is no guarantee the 53% target will be met.

Nova Scotia Power assumes there will be minor changes in demand for electricity over the next decade. This is overly optimistic.

Demand for electricity will increase as the province’s population continues to grow, electrically-intensive industries come to the province, and there is a uptake in electric vehicles. How this demand is met will determine Nova Scotia Power’s emissions.

Emissions from other sectors, such as transportation, will increase if drivers continue to opt for light trucks rather than passenger cars. The lack of affordable zero-emission vehicles and the necessary charging infrastructure will also contribute to the continued use of liquid-fueled vehicles.

For the province to meet its climate goals, it must abandon its current ad hoc approach and develop a new energy strategy which explains how the transition to a low-emissions economy will be achieved while ensuring that Nova Scotians have access to secure supplies of affordable energy.

- 30 -

Larry Hughes is a professor at Dalhousie University.